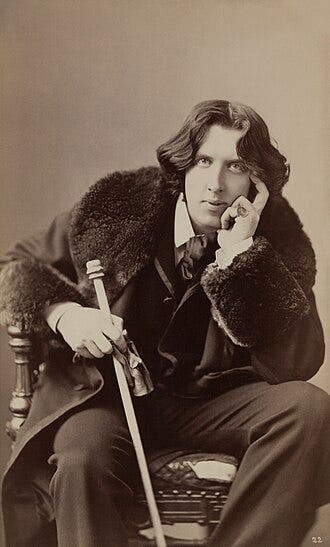

Oscar Wilde once quipped, “every saint has a past, every sinner has a future.”1

He also said, “skepticism is the beginning of faith.”2

Saints. Sinners. Skeptics.

I have been the last, I am the second, and I long to be the first.

skeptics

I was recently talking to a dear one, my beloved brother, who is a self proclaimed skeptic. His heart has been badly battered by this world, and his former church’s response to a difficult situation was less than kind. Even our family was not perhaps as kind as we should have been, more eager to prevent and fix than listen.

He has my compassion. I think I understand just about better than anyone why he struggles now. In the wake of the same tragedy - the death of our dad - I once proclaimed “I am either going to become a Catholic or an atheist, and I don’t care which.” I knew that my faith either had to become more than it had ever been, or be given up altogether. There was no long term plan for skepticism, no way I could live in the indecision.

Funnily enough - I think he came to the same place, more or less. He knew his faith had to grow or be given up. Neither of us became a Catholic or an atheist, settling for the perhaps lesser extremes of becoming an Anglican and a skeptic, respectively.

Why do we become skeptical?

There are many reasons, but a common one is that the whole of creation is deeply broken, even shattered in places, and yet we worship a God who claims to be all-loving and all-powerful.

If we can live with a belief in a God that is not always loving, or not always powerful, then there is no theodicy. But - if we see in Scripture the truth that God is all-loving and all-powerful, then we must wrestle with the brokenness around us. We must ask “why?”

My brother doesn’t hear others asking “why.” And he sees the faith of those unwilling to ask as something simple, thoughtless, and even shallow. Furthermore, he is the sort that asks questions when his dander is up. All of his questions truly come down to that “why.” The why God doesn’t stop all evil if he claims to be loving and powerful.

Now - I would say that my brother’s deafness is chosen. I know there are people in his world, good and godly people, who have suffered, who have asked why.

But the conclusion I have come to as a former skeptic myself, is that for all we might say we want an answer to the question “why did you allow this?” We don’t, not really. When I am suffering, what I want more than understanding why, is a belief that I am still seen, that someone is still with me. I don’t want to know “why.” I want to know “how?”

I want to know how to continue to believe in God’s goodness amid suffering.

I want to know how to live with my suffering.

God is the answer. His presence is the answer to our theodicy.

I cannot answer why God allows natural disasters and cancers. But I know He is The Answer. His presence answers every “how” we must endure in this life. And his presence will answer the “why” in the life to come.

When my toddler gets an “owie,” he doesn’t want to know why it happened. He wants me to draw him into my lap, to console and comfort. He doesn’t want an explanation, not really, he wants consolation. I don’t think we are so very different with the wounds we experience. We don’t really want an explanation for why God allowed it, we want his consolation. We want to know that he has seen our suffering, and he is drawing us closer to him in the midst of it.

He is the answer.

But it’s alright to ask the questions. It’s alright to be skeptical. I agree with Wilde that skepticism can be the beginning of faith. For me, at least, each season of skepticism has eventually been followed by a deeper faith. We must consider the reality of our world in order for our faith to grow. It’s just that the skeptic only looks at the reality of this world, and the believer looks for the reality beyond this world.

sinners

It is not fashionable to talk about sin. I usually talk about it in other language. This is partially because my audience includes some people less than comfortable with church-ese, so I prefer to use terms that are meaningful to them, such as “heart wounds,” and “brokenness.” But it is also partially because to talk about sin means to admit that I am a sinner.

Yes, wild & motherly audience, here is my confession. I am a sinner.

I daily must admit that I “have sinned in thought, word, and deed, in what I have done, and what I have left undone.”3 That’s the truth. There is never a time for confession where I don’t remember many sins I have committed, and on the few occasions I think “well, I haven’t done anything so very bad…” I realize that even in my confession I am committing the sin of pride.

Every sinner has a future.

This can sound either ominous or hopeful. For those of us floundering, crawling, stumbling, and tripping, but still trying to move towards sainthood - it sounds hopeful. We have a future, one that is beyond our current struggle with sin. But for those of us complacent in our sin, what sort of future is it?

Not a good one. Beyond fear of the eternal consequences, there are temporal ones. We have all seen how sin damages - it can destroy homes, careers, health, life, relationships, and eventually rot our souls.

Sin is not content to stay confined. It likes to infect every part of us. Our choice is to stumble towards God, failing often, but being strengthened by his presence, or to choose our own way, perhaps seeming to walk with our heads held high, but leaving destruction in our wake.

For as easy as it would be to point at others and talk about the devastation their sin has caused, the reality for each of us sinners is that that could easily become us. If we allow our sin to remain, even in a small area of our lives, it will try to consume us, and everything good around us.

Even the ‘little sins’ that I am so easy to dismiss - how I often respond to my circumstances with worry rather than prayer, how I often respond with pride rather than compassion when I see another’s failing, how I often snap in frustration rather than respond with gentleness when I face daily difficulties. All of these sins have the power to hurt me and others deeply, damaging relationships, and leading me even deeper into sin to excuse my behavior.

Even the fact that I tend to speed when I am running late for church is a sin. God asks us to obey the authorities in place, in as much as they don’t contradict the faith. As much as I would like to come up with a biblical justification for going 70 mph rather than 55 mph because I am ‘going with the flow of traffic’ by which I mean there are no other cars on the road so I can get away with it, I can’t.

We are all sinners, but we all have a future.

Oscar Wilde by Napoleon Sarony, albumen print on card mount, sheet 30.6 x 18.4 cm, on mount 33 x 19 cm. Notes 1045 U.S. Copyright Office. Title from item. No. 22. Copyright by N. Sarony.

saints

Every saint has a past.

I love to read about saints’ lives. We have quite a few storybooks in our house about the saints, and for Little Man’s first All Hallow’s Eve, I dressed him up as St. Francis, complete with little plush wolf.

Leon Bloy, Catholic novelist, concludes one of his works with, “the only real sadness, the only real failure, the only great tragedy in life, is to not become a saint.”

I think about this quote often. I know I would like to believe it, to believe that all other griefs, failures, and tragedies pale in comparison to the one of which I might fall short - becoming a saint. I want to have such a zeal for God, such a passion for becoming more Christ-like that nothing else in this world can diminish my longing for him.

But when I consider my past, including my sadness, failures, and tragedies, I struggle. My past doesn’t seem to be an auspicious start towards sainthood.

I have a history of unforgiveness, pride, bitterness, and ever so much fear. I have never known - except for short seasons - what it is like to live in a truly safe home, one without abuse. I have a propensity for creating chaos wherever I go, from getting locked into places like an inner city library that made Alcatraz look friendly, to fainting during my confirmation and having to be carried out of the service, to becoming pregnant when doctors say it’s impossible.

Sin. Abuse. Chaos.

Sainthood? Perhaps I should consider just survival-hood? But alas - my convictions and ideals run deeper than my sense, so I could never settle for such a meagre existence.

And I think that’s one of the misconceptions about the pursuit of holiness. We imagine it often as an arduous, painful task - and it is. We also imagine it is one that we will fail repeatedly, and and may not be ‘cut out for’ - and it is.

Jesus calls us to ‘take up our cross’ and follow him. The cross is an instrument of torture and death; it is no light burden.

But - just as the cross, an instrument of torture and death, has become a sign of God’s magnanimous salvation, so too, our lives, once full of pain and sin, can become a source of light to others.

Because the same Jesus who calls us to take up our cross, also promises that he wants to give us an abundant life. I don’t mean abundance in a prosperity gospel sense. But rather, a life bursting with his presence, and his goodness, his presence amid our trials. And his presence is all we ultimately want. It is no meagre existence if there is the experience of the fullness of God’s love.

Every heart, knowingly or unknowingly, no matter its call or cry, is searching for The Answer, is searching for His Presence.

So where do we stay?

As skeptics, wailing in the night, asking questions, but refusing to hear The Answer?

As sinners, pursuing our own desires, and refusing to consider our futures?

Or as saints, (well… saints in the making), wholeheartedly seeking His Presence, knowing it is the only answer for our doubts and our sin, the only way to have an existence that is beyond mere survival-hood?

Wilde, Oscar. 1893. A Woman of No Importance.

Wilde, Oscar. 1890. The Picture of Dorian Gray.

The Book of Common Prayer.